Thesis

Annual global emissions were around 40 billion tons as of 2023. The Paris Agreement, which was put into effect in November 2023, aimed to coordinate a global effort to limit the increase in Earth’s average temperature to less than 2 degrees Celsius (°C) above pre-industrial levels. Each country agreed to work together to limit the increase in global temperatures to less than 1.5 degrees by the end of the century.

To prevent global temperatures from rising 1.5°C-2°C above pre-industrial levels will most likely require about 30 gigatons of emission reductions along with 10 gigatons of annual carbon removal by 2050. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), backed by the UN, has assessed four paths to preventing temperatures from rising 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. All four paths require varying levels of negative emissions, that is, carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

Direct air capture (DAC) has emerged as the frontrunner in the race to create cost-effective negative emissions. There is only a single CO2 molecule found in every 2.5K molecules of the Earth’s atmosphere (0.04% air concentration), and identifying it and removing it is like removing a single drop of ink from a bathtub — a very difficult task. But, thanks to recent advances, DAC technology has been said to be entering its “awkward teenage years” where it has now become technically feasible and is now addressing the challenge of achieving implementation at scale.

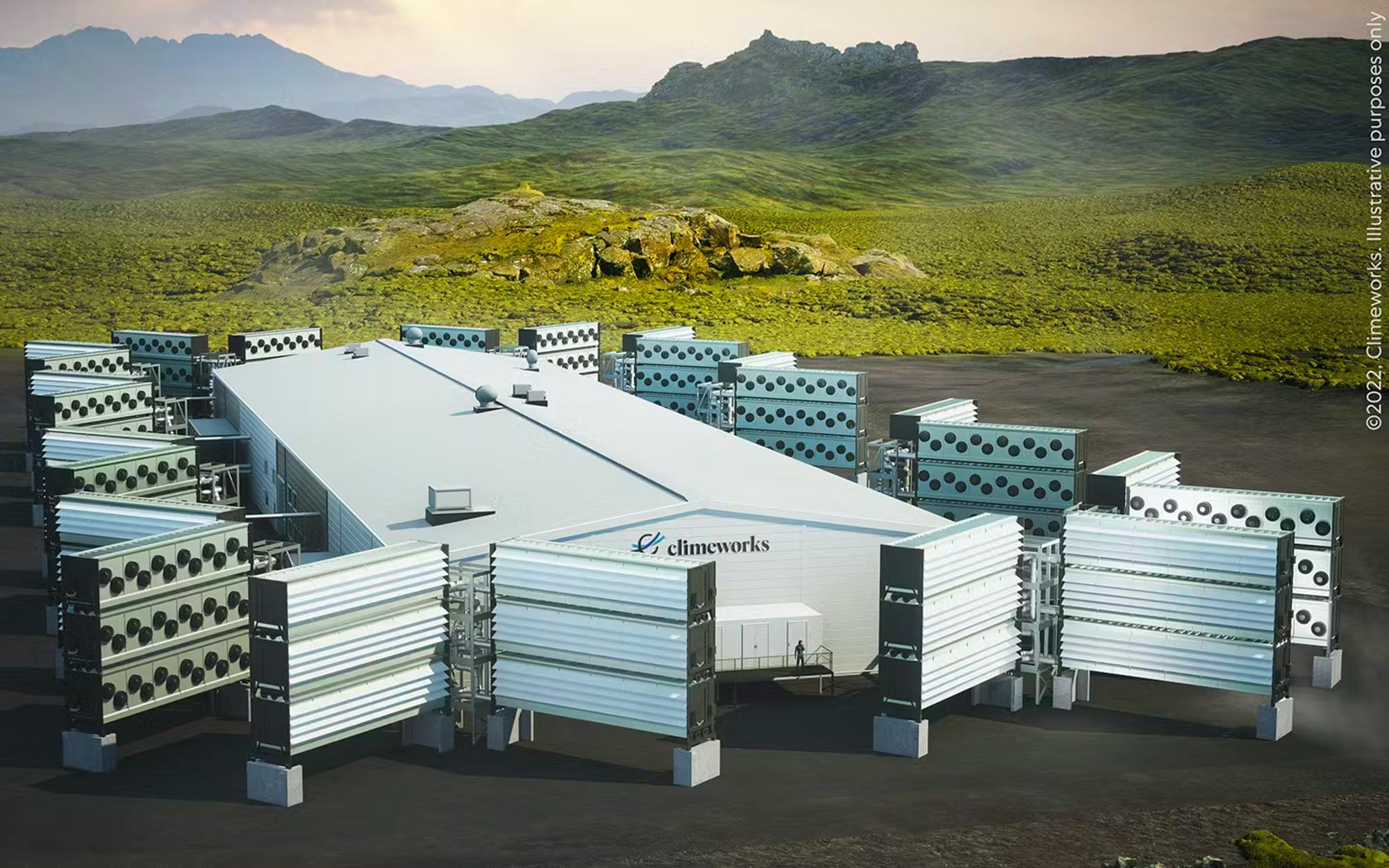

Climeworks, a Swiss company, is at the forefront of this effort. The company uses modular fans to blow air over CO2 filters, removing carbon from the atmosphere and working with partners to permanently store it underground. As the first company to extract carbon from the air and sell it as a product starting in 2017, Climeworks has been at the bleeding edge of DAC innovation for some time.

Founding Story

Source: ETH Life

Climeworks was Founded in 2009 by Christoph Gebald and Jan Wurzbacher who continue to act as co-CEOs as of January 2024. The two met on their first day as engineering students at ETH Zurich back in October 2003. At student orientation, the pair found out that they had both chosen the university for its academic reputation as well as its proximity to mountains full of ski and mountain biking trails. Both German, they began bonding over the fact that the Swiss dialect was difficult to understand, and finished the session intent on founding a company together.

While skiing in the Swiss Alps at one of their favorite resorts, Gebald and Wurzbacher were “shocked” by what they saw of retreating glaciers, and as a result “vowed to do everything they could to tackle climate change”. They began to work under Professor Aldo Steinfeld, who was researching ways to manufacture synthetic fuels using carbon dioxide, as graduate students. Working under Steinfeld, they developed a prototype for carbon capture based on submarine parts that captured one-half of a gram of CO2 from the atmosphere after a full day. It wasn’t much, but it was proof that it worked.

In 2009, the duo secured their first funding for the project — $300K from a Swiss foundation, and Climeworks spun off from the University to become its own organization. Climeworks was created at a time of alternating optimism and pessimism around the viability of direct air capture. In 2011, the American Physical Society released a report which cast doubt on the viability of DAC as a cost-effective strategy. As a result, although Climeworks was able to raise a further $2 million in funding, the company’s investors placed heavy pressure on the founders to produce results quickly.

At the end of 2012, Climeworks announced its demonstration plant with a projected capacity of just 1 ton of carbon dioxide per year. After successfully proving its hypothesis, the company moved on to pursue a 50-ton-per-year machine with the goal of reaching a gigaton scale by 2050.

Product

One way of conceptualizing carbon emissions and their impact on the atmosphere is the bathtub model: since more water is pouring into the tub (carbon emissions) than the earth can drain (via carbon sinks), it causes spills over the edge of the tub (climate change). Therefore, one way to prevent overflows is to reduce the amount of water going in (lower emissions). The other is to increase the size of the drain (via, for example, DAC). The latter is what Climeworks is focused on.

Direct Air Capture

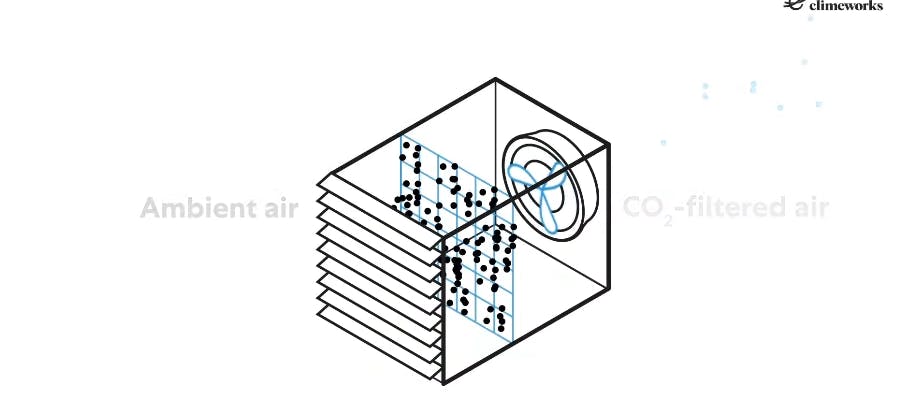

Source: Climeworks

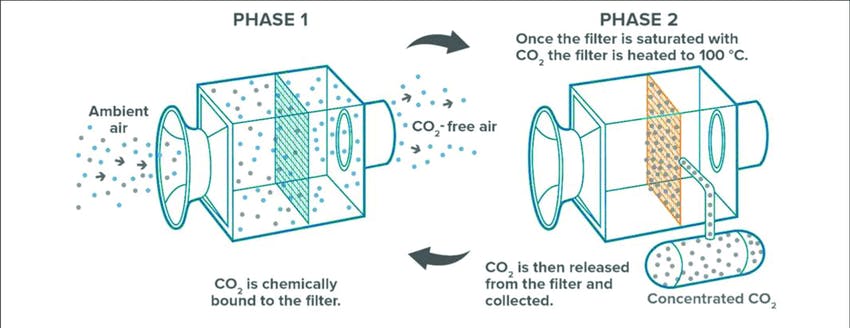

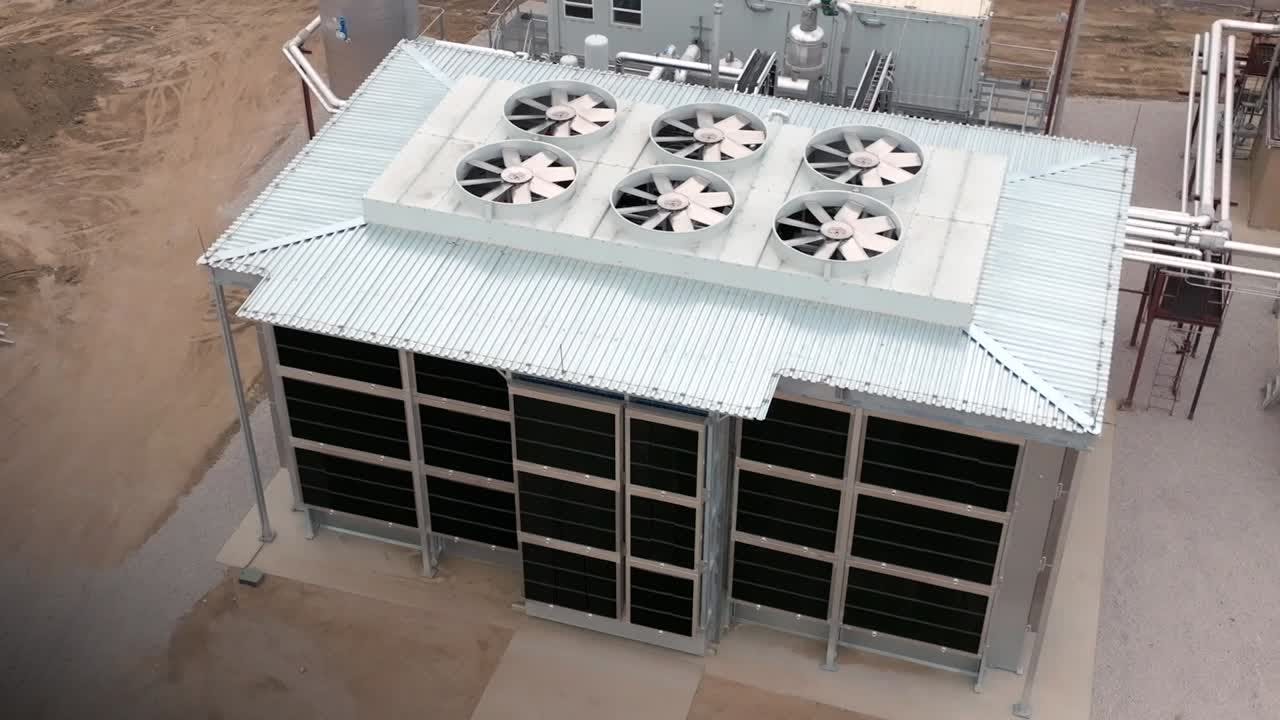

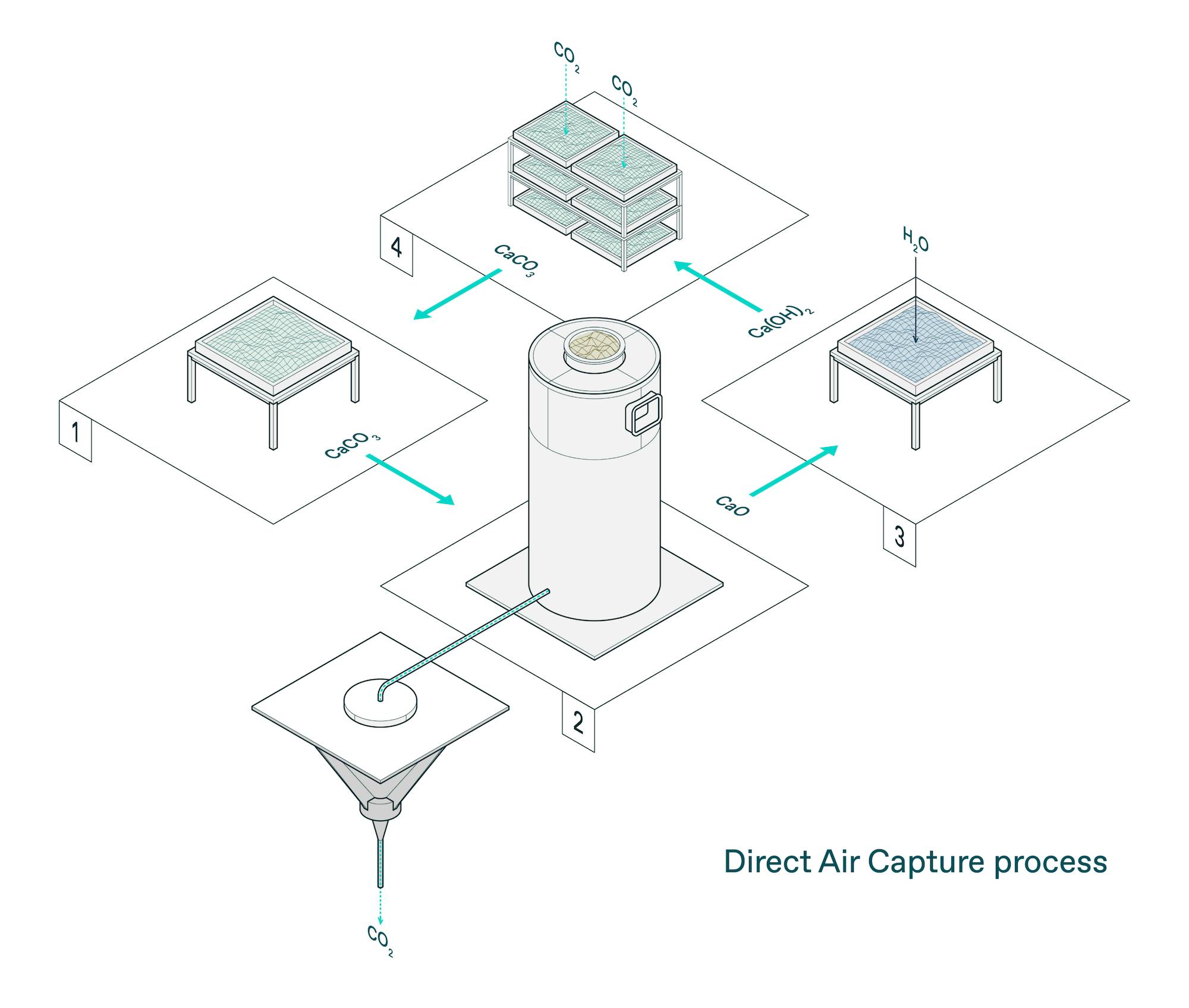

The first phase of Climeworks’ “cyclic absorption desorption” process uses a patented photo material to capture CO2 on its surface as ambient air passes over. Large fans push air over the pores of the amine-based sorbent material, capturing CO2 until the filter is saturated — like water being absorbed by a sponge.

The modules are then autonomously closed and heated to 100°C, causing the sorbent to release the CO2 as pure gas. Vacuums extract the concentrated CO2 gas from the modules and bring it to a central location to be purified and compressed before sending it to storage partners. Because the CO2 concentration is so low in ambient air, it requires extensive electricity to fill and heat the filter. Using fossil fuels would negate the impact, so the entire process is powered by renewable energy, energy-from-waste, and other waste heat.

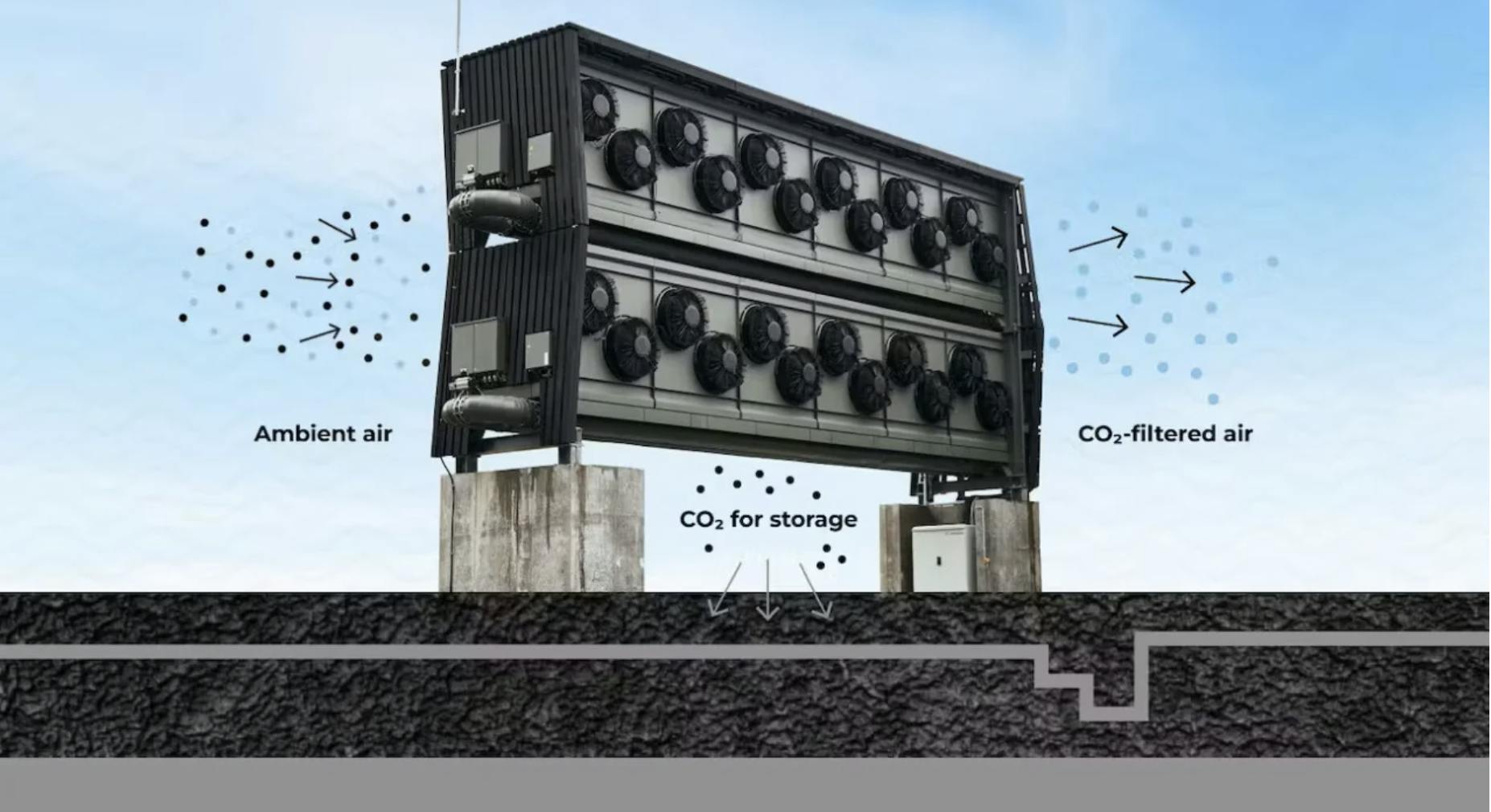

Source: ResearchGate

Systems are created by mounting multiple modules together to create a wall of fans. The modularity of a Climeworks plant has two primary advantages. First, installation costs and efforts are reduced once the machinery reaches the site, creating cost advantages at scale. Second, modularity lends itself well to quick innovation.

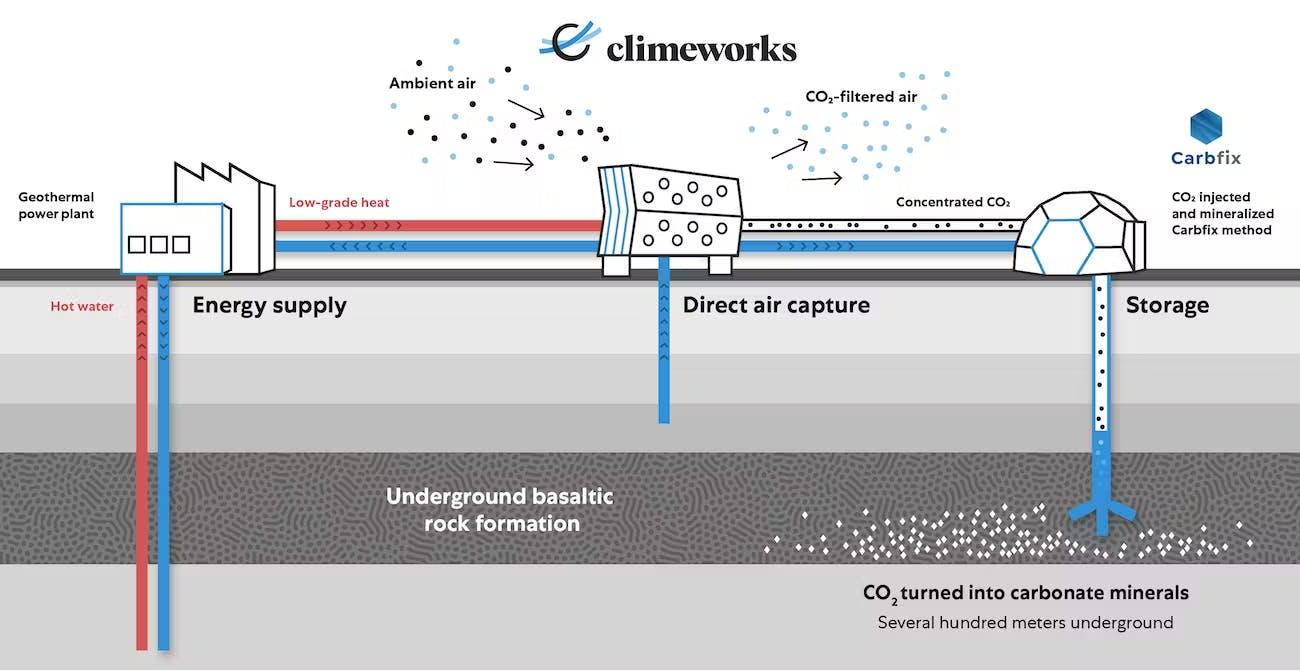

Source: Climeworks

Carbfix’s Carbon Storage

While Climeworks has provided its purified CO2 to beverage companies, greenhouses, and other businesses in the past, sequestered CO2 is now sent to Carbfix, a long-term carbon storage company.

Source: Climeworks

After receiving the compressed gas via an underground pipeline, Carbfix combines each ton of CO2 with 27 tons of water, creating a “sparkling water” solution. This solution is piped underground into bedrock where it reacts with the stone, dissolving metals out of the rock which combine with the CO2 to create stone. The result is calcium carbonate, a white stone that fills in the pores of basaltic rock.

Flagship sites including Climeworks’s “Orca” facility and future Mammoth plant are located in Iceland just down the road from a geothermal energy plant. The combination of renewable energy and the surrounding basaltic rock in Hellisheiði provides ample areas for storage, making Iceland an ideal starting location.

Product Evolution

In 2009, Climeworks's initial technology was only able to remove half a gram of C02 after a full day. The company has made meaningful progress since then, starting with Capricorn which was finalized in 2015, sequestering 900 tons of CO2 every year. The system of 18 fans offsets the equivalent emissions of four freight trucks annually.

Source: Climeworks

Prior to this, Climeworks built Arctic Fox in October 2017, which was a pilot project for its next large-scale site, Orca. Arctic Fox consisted of a single fan and could only remove 50 tons of CO2 annually. The company learned from this to help build Orca in September 2021, which the company sees as an important milestone and has described as “the world’s first and largest direct air capture and storage plant”. Removing 4K tons of CO2 per year, Orca represents a 344% increase in capacity in the six years since Capricorn was constructed. Orca was named after both killer whales and the Icelandic word for “energy”, Orka.

While Orca represents a step forward in terms of the scalability of DAC, its annual impact still only offsets the equivalent of 3 seconds of human activity, the annual emissions of 250 US residents, or 600 European residents in terms of cumulative emissions. Orca was Climeworks’ 16th installation across Europe, but the first to store carbon instead of recycling it, thanks to the partnership with Carbfix.

Source: The Verge

Climeworks’s forthcoming Mammoth plant is projected to be capable of removing 36K tons of carbon by 2024, which is 9X the capacity of Orca. This facility will contain 12 sets of systems, each set containing two walls of 18 fans. This represents the company’s 18th project and second commercial DAC and storage facility. Located in Iceland, the project kicked off in June 2022 with an expected construction time of 18-24 months.

Source: Climeworks

Climeworks is optimistic about its plans to reach multi-megaton (millions of tons) capacity by 2030 and gigaton (billions of tons) capacity by 2050 when the metaphorical Mount Everest summit push will take place.

Market

Customer

Early on, Climeworks began by selling its proof-of-concept purified CO2 to a greenhouse close to the facility which used the CO2 to boost crop yield. The gas was also sold to Coca-Cola to add bubbles to VALSER Sparkling Water and to Aether which uses carbon to create diamonds. In an effort to decrease supply chain complexity, the number of customers, and the amount of carbon being rereleased back into the atmosphere, Climeworks announced in 2022 that it would pivot to completely focus on permanently storing carbon underground.

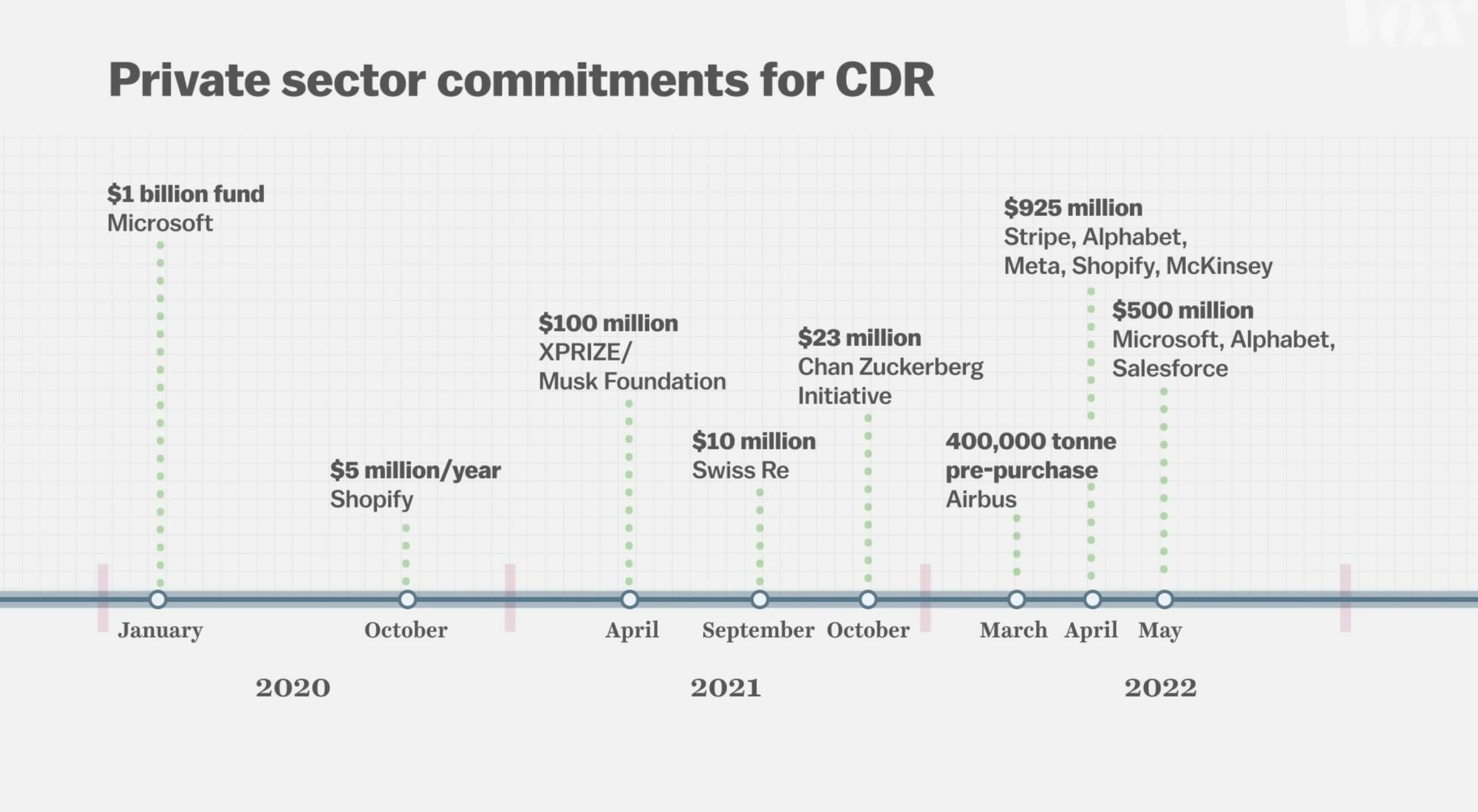

Today, Climeworks services the voluntary carbon market: i.e. businesses and individuals looking to offset their carbon emissions. Such groups are not required by law to offset emissions but do so voluntarily, either to drive a sustainable brand image to attract new customers or to prepare for future regulation or tax incentives. Corporations working with Climeworks as of January 2024 include Microsoft, Stripe, BCG, Swiss Re, Shopify, UBS, Zendesk, JP Morgan Chase & Co, Accenture, and more. Overall, the private sector demand for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) has seen a large influx since 2020.

Source: Vox

Climeworks also has a subscription model for individuals, starting at one euro per kilogram of CO2 captured, for anyone looking to offset their own emissions. For the average European leaving an annual carbon footprint of somewhere around 5 tons of CO2, it would cost 5K euros per year to offset their emissions via Climeworks.

Market Size

The carbon capture, storage, and utilization market was valued at just $3 billion in 2022, but it is projected to grow quickly. Projections vary wildly on the future of the market, everything from $14.2 billion by 2030 on the low end to $135 billion on the high end. Meanwhile, the carbon offsets market could reach as high as $1 trillion by 2037.

According to Climeworks co-CEO Wurzbacher, the predominant driver of the CDR market continues to be the voluntary carbon market. Contributions from this have amounted to the capture of less than 0.01% of global annual carbon emissions — reaching just 1% of global emissions would require 750K shipping containers filled with CO2 collectors, the same number of containers passing through the Shanghai Harbor every two weeks. As Wurzbacher acknowledges, policy action will likely be needed for the market to reach scale:

"The voluntary market for carbon removal will bring us to millions of tons, maybe ten million tons, maybe more. Public instruments will have to bring us from tens of millions of tons to billions of tons.”

There are signs that governments may increasingly contribute towards this market. The US Government and countries around the world were offering billions of dollars in funding for DAC and other CDR technologies as of 2023, but carbon taxes and limits are less common.

The primary obstacles for the DAC market are scalability and trust. As mentioned previously, DAC companies are barely making a dent in global emissions as is and the amount of capital to build facilities and purchase their services is substantial. Climeworks and others in CDR must also rely on third-party verification services to validate their numbers to customers and other interested parties.

Competition

Carbon Engineering: Founded in 2009, the same year as Climeworks, Canada-based Carbon Engineering has raised $110.4 million. As of 2021, Carbon Engineering was removing about 300 tons of CO2 annually, notably less than Climeworks. However, the company’s largest project to date hopes to be removing 500K tons every year in Texas starting in late 2024 with the ability to scale to one million tons thereafter. If Carbon Engineering is able to achieve this, it would represent a massive leap ahead of Climeworks in terms of capacity.

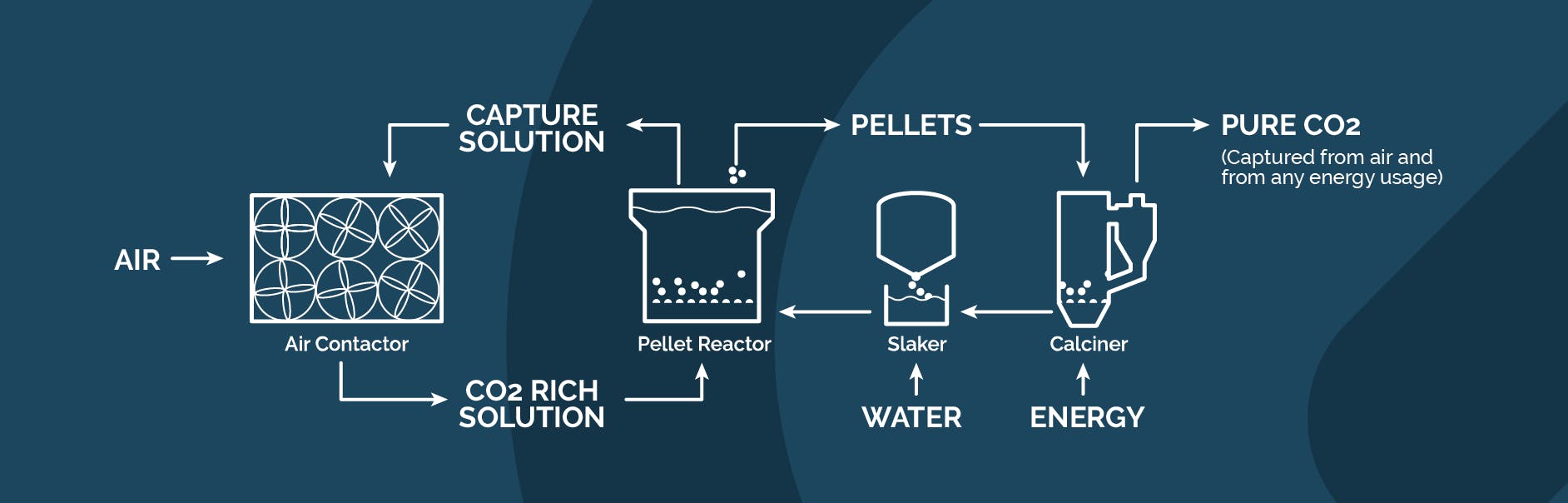

While both Climeworks and Carbon Engineering deliver concentrated CO2 gas as an end product, their processes differ slightly. Carbon Engineering uses a potassium hydroxide solution, instead of an amine-based sorbent like Climeworks, which is run over a plastic surface as air from fans is passed through. The carbonate salt solution is taken through a water treatment process to produce carbon-concentrated pellets which are heated to release the CO2. Both the salt and the carbon-capturing chemical are then derived for reuse.

Source: Carbon Engineering

Instead of simply storing the carbon and selling carbon credits, Carbon Engineering has partnered with Occidental Petroleum Corp. to assist in enhanced oil recovery at the new Texas facility. Purified carbon gas is injected into active oil fields, pushing oil to the surface quicker than traditional methods. Although helping recover oil may seem like a paradoxical use of direct air capture technology, Steve Oldham, Carbon Engineer’s CEO, has stated that the long-term vision is to move beyond enhanced oil recovery, but the company needs customers during the early stages.

Global Thermostat: Founded in 2010, just one year after Climeworks and Carbon Engineering, this Colorado based company just reached a 1K ton annual capacity in 2023. Co-founders Peter Eisenberger and Graciela Chichlinisky were pushed out and replaced by current CEO Paul Nahi in 2022. One major benefit Global Thermostat holds is Department of Energy (DOE) funding, the primary funder of its next model still under development which hopes to reach megaton scale.

The process used to sequester CO2 employed by Global Thermostat is similar to Climeworks’s process, though its system looks slightly different. A liquid amine-based solvent absorbs the CO2 which is then heated to release the gas. Climeworks is known for using waste heat, but Global Thermostat makes no statement about the source of its heat. Scalability and low prices seem to be the primary advantage of the company’s approach according to previous CEO Peter Eisenberger who believed the company could reach prices as low as $50 per ton.

Source: Global Thermostat

Poor management has been considered the reason for the company’s lack of success in scaling its capacity as well as relatively low funding, having raised a total of $88 million.

Heirloom: Heirloom was founded in 2020 and as of 2024 it has raised $54.3 million in total funding. Heirloom is targeting a similar customer base to Climeworks and because of relatively cheap prices, the companies actually share multiple accounts including Microsoft, Stripe, and Shopify. By 2035, Heirloom hopes to have removed one billion tons of CO2, which it’s able to accomplish, would demonstrate a level of scale that traditional DAC methods have not seen.

While Heirloom injects carbon underground just like Climeworks, the company has also partnered with CarbonCure to inject the carbon into cement, permanently sequestering carbon in the built environment. Cement abounds in the modern world and because carbon actually makes the building material stronger, it represents a compelling use case of sequestered carbon.

Heirloom’s process is unique within the market. Instead of using fans and a solvent material, Heirloom uses crushed limestone and kilns. The crushed limestone is placed in a kiln (powered by renewable energy) which uses heat to separate CO2 from calcium oxide powder. Although limestone may seam like a limiting factor to this process’s scalability, Heirloom has solves this by mixing calcium oxide powder with water which absorbs enough CO2 to convert itself back into limestone within three days, when it is ready to be placed back in the kiln.

Source: Heirloom

Business Model

As an emerging market, prices for a ton of carbon removed through DAC started high. Each ton removed by Climeworks fetches a price tag of around $1.2K, though that number drops to $600 per ton if purchased in bulk, presumably the larger side of the business. A portion of this income is distributed to Carbfix to finance the storage of the carbon.

Prices are so high because of the amount of money Climeworks has to invest in building facilities and the ensuing R&D to increase capacity for future facilities. Orca cost between $10 million and $15 million and the company admits that the main focus for this project was learning to increase the scale of future projects, not the price. As facilities grow larger (more fans), the cost per ton removed will decrease due to economies of scale. The US Department of Energy (DOE) is seeking carbon credit costs closer to $100, but no DAC facility is close to reaching this target.

Price reductions would allow more voluntary purchasers to join the carbon offsets market, which could broaden the company’s subscriber base. Wurzbacher predicts that private subscribers will eventually make up half of Climeworks’s revenue. If prices fell to just $100 per ton, the average European could offset their personal emissions for just $500 per year, half of what they pay on average for annual car insurance.

Traction

The company has steadily scaled its capacity for carbon capture. At the beginning in 2009, it took a full day just to capture half a gram of carbon using its process. Its Orca facility launched in September 2021 has a capture capacity of up to 4K tons of CO2 per year, and its Mammoth plant will be able to capture up to 36K tons per year, representing an almost order-of-magnitude improvement.

When it was founded, Climeworks stated that its objective was to capture 1% of global emissions by 2025 but after realizing that 300 million tons would not be achievable, this goal was adjusted to one million tons by 2030. When asked about the large decrease in expected outcomes, Wurzbacher said it has nothing to do with demand:

"The timeline has changed as it takes longer than we originally anticipated to build up an entire industry… Already the demand for carbon removal at Orca is so high that we have decided to scale up this plant and build a roughly 10 times larger plant in about three years.”

Due to the large amounts of capital injection in 2022, Gebald believes Climeworks will go from 180 employees to 400 by the end of 2023. As of 2021, the company was still unprofitable.

Valuation

In April 2022, Climeworks announced it had raised $650 million in a private equity deal at an undisclosed valuation, by far the largest sum of money raised in CDR history. The round was led by Partners Group and GIC with additional participation from Baillie Gifford, Carbon Removal Partners, Global Founders Capital, John Doerr, M&G, Swiss Re, and others. Having finished Orca, and thus phasing out Capricorn, this money will be used to develop Mammoth and future sites to help Climeworks achieve megaton scale in its capture capacity. Part of the company’s funding also comes from debt financing from Microsoft’s climate innovation fund. This round brought Climeworks’s total funding to $862.7 million as of January 2024.

Key Opportunities

Government Regulation & Funding

The voluntary carbon market will likely not be enough to fund gigaton-scale CDR. For that many tons of carbon to be financed, companies must be required to offset their emissions via policy. In alignment with global goals, the first step towards mandatory offsets is mandatory carbon footprint reporting. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) was passed by the EU in Spring 2022 and requires nearly 50K companies (based on size, revenue, assets, and more) to report their GHG emissions as early as fiscal year 2024. Similarly, California became the first US state to pass carbon reporting laws in September 2023 which will go into effect in 2026.

Presumably, if and when GHG reporting is mandated on a global scale, companies will be incentivized to lower their emissions, and eventually offset lingering pollutants. This is the progression that Climeworks is depending on. In the meantime, governments are focused on pushing funding to improve decarbonization and carbon removal technology. For example, The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) passed by the US Government in 2022 potentially contains billions in government-backed incentives for carbon removal efforts in addition to the $3.5 billion in funding for four national DAC hubs. These sites are designed to provide companies with areas to experiment and improve carbon capture and storage technology in the US.

Once carbon offsetting becomes mandatory for companies, governments will most likely offer tax credits for every ton removed, or penalize companies that refuse to offset emissions. The IRA expanded US tax credits to $180 per ton of CO2e removed, though there are various stipulations companies should be aware of while choosing their credit supplier. Tax incentives, mandatory reporting and reductions, and more would lead to escalating demand for Climeworks.

Redefining Carbon Emissions as Waste

Waste products often include garbage, sewage, and other items that pose a threat to a population’s health if left untreated. Municipalities use taxes to fund the collection and processing of these items to avoid disease and uncleanliness. Klaus Lackner, the pioneer for direct air capture technologies, believes that carbon should be treated in the same way since it has the same effects if left untreated.

Some governments agree. Canada is an investor in Carbon Engineering and the European Union is funding Climeworks. If air quality deterioration, natural disaster intensity, and food system collapse reach certain levels, governments may increasingly treat carbon as a waste product, using municipal, state, or federal tax money to finance CDR.

Expansion through Adaption

One question around CDR is whether the earth contains enough space with perfect conditions like Iceland for efficient CDR and long-term carbon storage. The answer is probably no, but there are plenty of small tweaks to the process that could make many areas suitable. For example, Carbfix is researching ways to adapt its mineralization process to work well with other forms of rock, which could Climeworks to venture outside of volcanic land. Other companies like Charm Industrial are choosing to pump sequestered carbon into orphaned and closed oil wells, which there are plenty of in the US and around the world. Climeworks is also learning how to use saltwater for areas without sufficient freshwater, and as a general solution to avoid consuming the world’s dwindling freshwater supply.

The company could also investigate other areas to permanently sequester carbon such as partnering with companies like CarbonCure, as its competitor Heirloom has done. Additionally, Air Company converts sequestered carbon into alcohols and fuels sold as perfumes, sanitizers, and jet fuel. There are many partnerships that Climeworks can make beyond Carbfix and doing so will allow for growth and mitigate dependency risks.

Key Risks

Inability to Lower Costs

If 10 billion tons of CO2 are to be sequestered annually by 2050, at the optimistic price of $100 per ton, that would require $1 trillion of yearly investment. But, at the Climeworks DAC Summit in 2023, Wurzbacher told attendees that prices could remain as high as $300 by 2050.

Sam Fankhauser, professor of climate economics and policy at the University of Oxford, has questioned the viability of scaling CDR technology, saying that:

“It’s still expensive, still only at the pilot stage, and there’s still lots of technical and environmental questions, but this is essential technology."

When Climeworks decreased its carbon sequestration goals from 300 million tons to just 1 million tons in 2021, this did not inspire great confidence in the market. To make it worse, the company’s goal to drive prices below $300 per ton by 2050 was originally set for 2030. Achieving a lower price point will be essential to unlocking scale for DAC. Some non-DAC carbon offsets have achieved a $100 price point such as those from Patch and Pachama, but many of the credits offered struggle with debates around additionality, fraud, and permanence.

Summary

Climeworks stands at the forefront of the direct air capture market. Its forthcoming Mammoth plant, which began construction in June 2022, will sequester nearly 40K tons of carbon every year once operational. Most climate change prevention plans require anywhere from 5-10 gigatons of sequestered carbon annually by 2050 and Climeworks hopes to reach gigaton scale by that year. Selling mostly to customers looking to buy voluntary carbon offsets, Climeworks has seen rising demand, but it will likely take government regulation for its market to reach a new level of scale. Climeworks’s underlying technology has evolved to repeatedly increase capacity, and the biggest uncertainty it faces is around the growth of the carbon removal market as a whole.